Setting musical goals, designing a practice plan

JTM002: The organized and intentional pursuit of musical goals

Note to reader:

Moving forward, I’ll be posting my written Substack pieces one week before the video versions. You can expect the video version of this piece next Wednesday, March 5th.

Otherwise, I hope you enjoy this piece thoroughly, and I appreciate you for supporting my work!

From Enthusiastic to Overwhelmed

I don’t think I was ever taught how to practice, or rather, how to be a practicing musician.

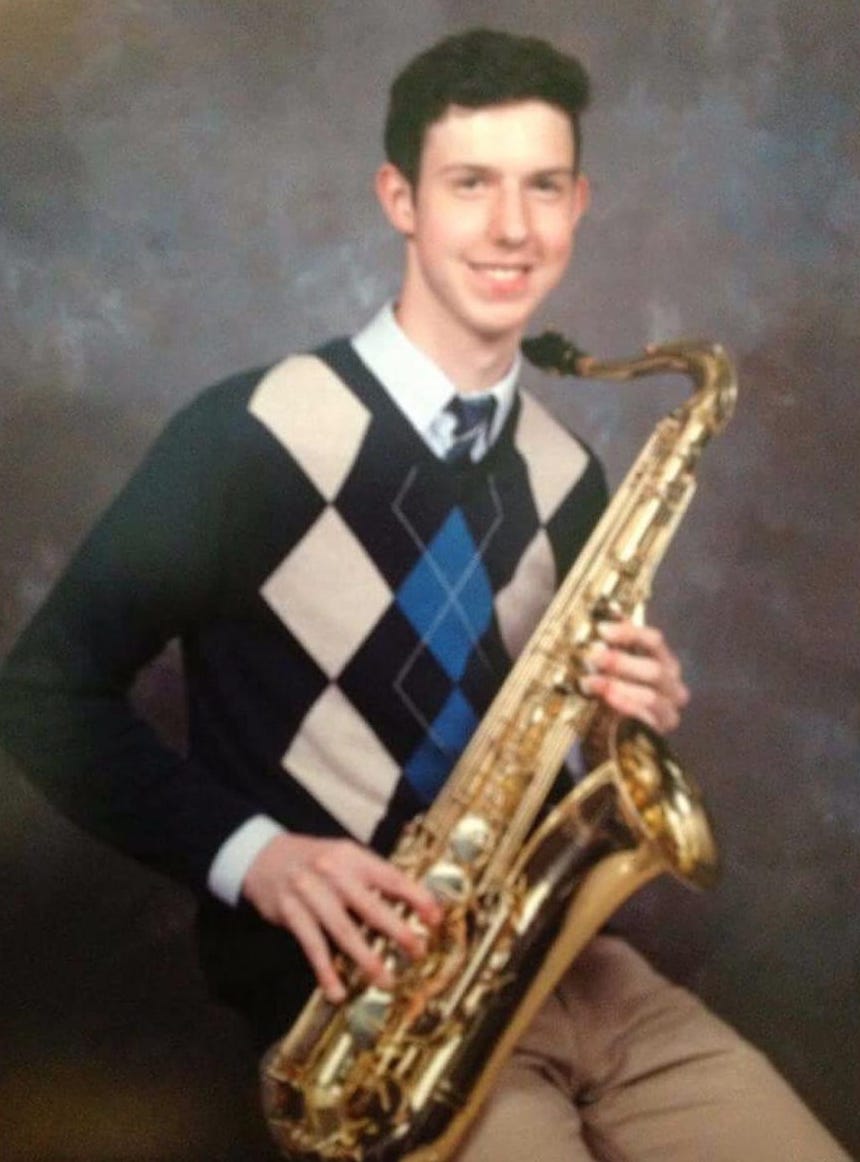

I began playing music as an 8 year old after my grandparents gifted me a guitar. As I continued playing and picking up new instruments throughout my school years, the kinds of music I played, or how I practiced was mostly dictated by my whims. I would learn songs I liked, my teachers would help me work on things outside of my immediate interests, and eventually I was motivated to learn certain songs and techniques to play music with other people. I was naive about practice at this point. I didn't have a deep understanding of what it meant to be a practicing musician or how to structure my learning effectively.

At 18, I was a new fan of saxophonist Bob Reynolds (of John Mayer and Snarky Puppy). Having a budding YouTube channel, Bob offered to send voice notes answering subscriber questions. I asked for practice advice to which he responded, “Learn tunes, and transcribe solos.” This became my first intentional practice goal.

Shortly after receiving this advice, I came across Michael Brecker’s infamous 1984 masterclass at UNT. In the Q&A (26:48), Brecker is asked about how he approaches practice and briefly speaks about keeping a practice log (this notebook has since been published!)

Being an fan of Brecker, I decided to try it out for myself. I wrote the advice from Bob Reynolds on the first page of a notebook to serve as a sort of practice mantra—learn tunes, and transcribe solos—and in the following pages I kept notes of each practice session including my warmups, transcriptions, tunes, and even the amount of minutes I practiced (though this last one proved to be unhelpful).

Looking back, this was a pivotal moment in my development as a musician. The act of documenting my practice not only helped me stay accountable but also allowed me to see patterns in my learning process. This taught me that being intentional about practice was just as important as the practice itself.

As I continued in my pursuit, musical objectives stacked up and progress became murkier. As a senior in college, this is what a day in my practice regime looked like:

Top Tones for Saxophone

Saxophone Embouchure Exercises

Long Tones on Saxophone

Klosé Etudes for Saxophone

Transcribing lines/solos for classes/lessons

Learning the 2-3 new tunes of the week for repertoire class

Reviewing past tunes from repertoire class

Practicing tunes for Jazz Combos

Practicing charts for Big Bands (I was in 2)

Harmonics/Overtones on Flute and Clarinet

Rose Etudes for Clarinet

Etudes for Flute (I think Taffanel, but I am unsure)

From my freshman year to my senior year, my practice goals went from 2 to 12. As a college student with an abundance of practice time, I was actually able to do all of these things most days, but there was inevitable fall off — days where I could maybe accomplish 2-3 of these tasks, and the more obvious transition from college into the working work. I can also confidently say I retained much more with my initial 2 goals than I ever did when I had a dozen in front of me. Now, 11 years later at 29, I approach practice very differently:

I understand good practice to simply be the organized and intentional pursuit of a musical goal.

The following method offers a structured approach to designing a practice routine that aligns with both your musical aspirations and practical constraints.

Designing and Implementing Your Practice Plan

Step #1: Take a moment to reflect

This is the intention piece from my earlier definition of good practice. Essentially this step encourages you to exercise a bit of self reflection on your mindset, priorities, and bandwidth.

Reflect on your mindset

In reflecting on my own development, along with the development of my students, I’ve found there to be 3 common mindsets among most musicians:

The Free Spirit — I practice because I enjoy music.

This mindset is characterized by pure enthusiasm and exploration. Like a child discovering their first instrument, the novice approaches music with wonder and curiosity. They practice what interests them, learn songs they love, and are driven by the simple joy of making music. While this approach lacks structure, it maintains the essential spark that drew them to music in the first place.

The Formalist — I practice because I wish to be great.

This mindset is focused on technical mastery and improvement. They often have structured practice routines, specific goals, and measure progress through achievements like performances or exams. This mindset is crucial for developing discipline and expertise, but can sometimes lead to burnout if not balanced with the joy of playing.

The Devotee — I practice because I wish to serve the music.

This evolved perspective transcends personal achievement. The musician understands that practice is about honoring the art form and contributing meaningfully to the musical tradition. Their practice focuses on deeper understanding, interpretation, and the ability to communicate through their instrument. They balance technical maintenance with artistic growth, always grounded in service of the music itself.

There is no correct mindset to fall into. I can personally say I’ve found myself in each of these mindsets throughout my development, and I would even venture to say you need a healthy balance of each to move through long periods of musical growth.

Reflect on your priorities

Write out 3-5 “I” statements about your current musicianship, and stay absolutely neutral—think about it like a doctor conducting an annual health assessment. Here are some examples:

I can play major scales in all 12 keys but not all at the same speed.

I have a good tone on my instrument, but I have a hard time keeping it at soft volumes.

I can improvise in most keys but feel limited in E and B major.

Write out 3-5 “I” statements about your musical aspirations. Consider the following questions:

What are you genuinely interested in? What speaks to your soul and would feed you spiritually to know deeply?

What are your social music goals? Is there a jam you’ve wanted to start going to? Are there common tunes that would help facilitate your entrance to that environment? Are you hoping to form or join a group?

Reflect on your bandwidth

Take a moment to sit down with your schedule and determine a realistic practice schedule. Try to remove your ambition and emotions from this one and simply see what options are available to you. The amount of time you have available is not a measure of how good you can get, but rather what you can realistically take on. In learning any new material, repetition is crucial. That being said, it's better to have 4 days that you can practice for 5-10 minutes than 2 days that you can practice for an hour.

Step #2: Prepare your practice plan

Write a practice mantra. Treat this like a yoga mantra—keep it simple and affirmative, like my earlier example of “learn tunes, transcribe solos.” For broader musical skills, consider language like “improve my tone” or “strengthen my time.” Once you have a mantra, write it down in the beginning of a practice notebook. You will revisit and refine this monthly—it does not need to be perfect.

Schedule your practice sessions. This can be done in a written planner or in your phone calendar. As of late, I have been sitting down on Sunday evenings to schedule my practice for the week ahead. This works well for me because I have an firm idea of my teaching schedule, important projects, and other work that will also require a lot of attention, and I can schedule accordingly. You will want to consider your energy levels and other commitments. I personally have struggled to practice after a long day of work or after a social gathering—especially when drinks and other indulgences are involved.

Create a practice feeder. It is a major bummer to have the time to sit down to practice and realize you finished your previous tasks, haven’t chosen a new one yet, and need to spend time determining what is next. Having feeders—whether it be a list of pieces you want to learn, a playlist of recordings you want to transcribe bits of, or a stack of technique books you want to dive into. Here are a couple I keep:

I have a transcribe playlist in my Apple Music library as well as a notes app entry. When I hear a line I might want to transcribe I add it to the playlist and timestamp the line in my notes app.

I keep a repertoire list of pieces I know well, sort of know, and want to know. If I want to learn a new piece, review, or plan a performance, it’s all in that list.

Step #3: Practice and refine

The aim of the first 2 steps is to make step 3 as simple and clear as possible, because it can be the most challenging one. Remind yourself: all that is required is for you to sit down and execute the plan you set for yourself. You set a plan out of care for yourself. It does not require any additional ambition or self judgement, just your trust in and commitment to yourself.

Practice

Begin by reading through your practice mantra and deciding the specific exercise or piece of music you will work on.

Tell yourself “I will practice for at least 5 minutes.” This is a trick I learned from Effortless Mastery: the idea being that 5 minutes is a minimum threshold to get engaged in an activity, and more than likely you wont want to stop once you get to 5 minutes and it will turn to 10, 20, or even a half hour.

For longer sessions, consider something like the Pomodoro Technique where you mix 25 minutes of focused practice with a 5 minute break. We only have so much energy and attention and breaks will help you reenergize and refocus.

At the conclusion of your practice session write down what you worked on, and be specific. The next time you practice, read through your practice mantra and your last practice entry, and pick back up precisely where you left off.

Check in and refine

Set a date once per month to check in with yourself. Read through your practice journal from your mantra to your day to day logs. Note what seemed to progress and what took more time—remind yourself that none of this is necessarily good or bad or even a reflection of your work, but rather important information about how you learn. Here are some considerations:

Make note of any big wins—the positive affirmation of your work will go a long way!

Gently, consider what areas you made less progress than anticipated, and consider what improvements might be worth making the next round.

Assess whether you took on too much material, not enough, or just enough.

Rewrite your mantra (including any updates you may have) on the next page and head into the next round—rinse and repeat.

My Current Practice Plan

Just to give you an example of how I’m utilizing this, I wanted to give a glimpse into my practice log.

My current priorities are:

Improve my tone and time.

Revisit jazz standards I have gone fuzzy on over the years.

Expand my vocabulary especially in the realm of arpeggios, pentatonics, and chromatic vocabulary.

Because of this I’ve returned to an updated version of my original practice mantra—Improve tone and time, learn tunes, and transcribe solos. As of late, I am using a digital notebook through the app Good Notes, and I have my mantra on the first page like this:

Currently, I teach lessons on Monday-Thursday afternoons/evenings as well as Saturday during the day. So, I schedule my practice block from 12:30-2 each day. This window allows me to work on writing and recording projects in the morning, not bother my roommates or neighbors with sound too early or late, and harness my energy before it's exerted through teaching or working on projects.

I have two practice feeders at the moment—A list of 100 jazz standards (most of which I used to know and am relearning…) and a transcription playlist/notes app entry:

This is a log from one practice session. I worked on my time and tone with a rhythmic long tone exercise I’m developing, practiced the tunes “Out of Nowhere” and “Beautiful Love,” and took a line I transcribed from a Jackie McLean solo through 12 keys.

Closing Thoughts

In wrapping this piece up, I want to articulate that I don’t think there is such thing as a perfect practice plan. Life is constantly in flux, and there will be times when we fall short of our priorities. Regardless, putting a plan into effect helps us recalibrate and get back on track—just remember to be kind and patient with yourself!

As the late Leonard Bernstein wisely said:

"To achieve great things, two things are needed: a plan, and not quite enough time.”

This idea of feeders is really great. And, knowing what you're going to practice as you enter your practice session is great advice. As someone who has no formal music training, I appreciate the level of transparency that you share in this! Btw...Love to see the mention of Effortless Mastery. Maybe it's time for a re-read...

I came here from YouTube. I’ve been learning piano for about eight years - I’m not very good but passionate and loved hearing about your experience and the pressure you felt to succeed. Keep making vids.