Musical grammar

Scales and chords make people shudder. Visions of childhood piano lessons and colorful band room “incentive charts” may manifest for some. Scales and chords are often treated as musical ladders to climb—something considered important but without sufficient context.

There are books filled with scales and chords, countless youtube videos explaining them, and probably a PDF from your favorite music content creator claiming it will help you master them (wink, wink).

When I transferred to Purchase College as a third year student, it was quickly evident that I was not fluent in all 12 keys. In my first semester of a repertoire class we played every tune in 12 keys—this particular class had ~30 tunes over the semester. I fell on my face for the first month. Soon after, I devised a daily scale and arpeggio practice routine. By the next semester I was beginning to be able to take tunes through 12 keys on the fly, and more importantly it was a bit easier each time I tried.

I discovered a few things:

Scales and chords are like musical grammar

Understanding scales and chords is as much about your instrument as it is about your ability to think musically

All this to say, becoming fluent in scales and chords expands your musical potential. It did and still does for me.

This piece will include a PDF of the first half of exercises I’ve developed for free download. If you have the means to support my work consider becoming a paid subscriber so I can continue to publish resources of this nature.

What scales and chords really are

Scales and chords are abstractions—a way of codifying the melodic and harmonic building blocks of music. On their own scales and chords are not music but rather tools we can use to more deliberately make and play music.

When I was a young musician, I didn’t think much about how to systematically learn scales and chords. It felt like homework, and I was never exposed to the broader purpose. Now that I work with young musicians, I recognize the value of teaching scales and chords to developing creative musicians—folks hoping to open their ears, improvise, and compose.

In jazz music we talk a lot about improvisational vocabulary. Scales and chords are not vocabulary but rather the alphabet our tonal vocabulary is grounded in. Fluency in chords and scales makes everything a bit more logical and systematic.

Over the past year, I redefined how I first introduce chords and scales to students. With regular practice (at least 4 times per week), a student can build a foundation of basic scales and chords in 12 keys in 6 months or less.

Practice methodology

You’ll find that certain domains within your practice will be long (a marathon) while others are shorter (a sprint). This particular practice method is a sprint: allowing you to tangibly change your playing in a short period of time.

The roadmap I’ve worked out is broken up into one month increments. Each month, you’ll focus on 1-3 keys and their respective scales and chords. The key to this practice plan is to show up consistently—4 times per week at minimum. At the beginning of the month, it will take about 5 minutes, and at the end, it will increase to about 15 minutes.

Month-to-Month Roadmap

Month 1: C and G Major, A and E Minor

Month 2: D and A Major, B and F# Minor

Month 3: E Major, C# Minor, and the Chromatic Scale

Month 4: B and F Major, G# and D Minor

Month 5: Bb and Eb Major, G and C Minor

Month 6: F#/Gb, C#/Db, and Ab Major, Eb, Bb and F Minor

Week-to-Week Roadmap

Week 1

5 note scales: Do-Sol, in C major, G major, A minor, and E minor. Play them with a consistent pulse against time (metronome, backing track, etc.) for about a minute each. If you play an instrument where your voice is freed up, say the notes while you play them.

Week 2

Continue to start with the 5 note scales—if these feel easy, your practice is beginning to show its value! Reviewing these helps build continuity into your musical memory.

Full scales: Do-Do, in the same keys as week 1. Continue to play these with a consistent pulse against time for 1-2 minutes each.

If you have an instrument with a big range, try the scales in 2 octaves.

If you play an instrument where your voice is freed up, say the notes while you play them.

Weeks 3-4

Continue to review the 5 note and full scales. This part will take only a short amount of time in your daily routine as they develop in your musical memory.

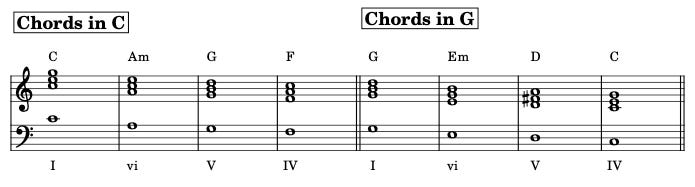

Chords: There are 4 particular chords you will study in this exercise—the I, IV, V, and vi. They’re everywhere, and knowing them deeply will get you a ton of mileage musically. What’s more—the chords repeat in other keys under different context. For example, an E minor chord in G major is the vi chord but in C major it’s the iii chord. Over the course of this exercise you will learn every chord (both major and minor) in all 12 keys with the exception of diminished vii chord.

For the exercise, you will write a chord progression using these chords— start with 4 chords, but feel free to get adventurous once you're comfortable. For the chord progression you wrote, choose chord inversions that make for smooth voice leading. Don't worry about following counterpoint rules, just make it sound nice.

On melodic instruments (saxophone, trumpet, violin, etc.), play the arpeggios with a consistent pulse against time.

On harmonic instruments (guitar, piano, etc.), play both the full chords and the arpeggios with a consistent pulse against time.

Instrument Specific Notes

As mentioned earlier, the primary aim of improving your scale and chord knowledge is to expand your musical mind. This will better facilitate collaboration with other musicians and help you connect the dots in your own musical ventures.

It is still important that you aim for good instrumental technique when studying this material:

On piano, you’ll want to play all of these exercises in 2 hands. The fingers you use for each scale is important. If you need a more robust resource for the piano fingers, consider using Alfred’s Scales and Arpeggios book.

On guitar and bass, you are riddled with multiple positions for everything you play. I would encourage folks on these instruments to investigate the CAGED System. With this exercise, you can spread out each position to match with the monthly layout: learn C and G position the first month when you work on the C and G scales, then D and A in the second month, and E in the third month.

On wind instruments, we are often playing transposed parts. I’ve never met a horn player who didn’t first learn the concert Bb and Eb keys, and I’m assuming that won't change anytime soon. However, one of the best skills I’ve learned as a horn player is being able to transpose on the fly to play with concert instruments. So, consider trying to learn your concert C and G scales in the first month by sight-transposing (reading the concert notes, but playing the transposed pitches). This will be really hard at first, then second nature (I don’t even write transposed parts for myself or anyone I work with!)

Learning scales and keys

The above section is merely a brief explainer of the full practice plan. If you’re looking to dive in, here is the full exercise available for free download:

If you have any questions, leave a comment below and I will do my best to guide you in your own practice!

What’s next

You can expect a video essay version of this piece with demos of each step next Wednesday, April 30th!

Following that, I have a follow-up piece on the topic of Mastering Key Centers for when you are ready to move beyond the techniques of this piece and work on developing total flexibility in 12 keys, triads, 7th chords, and various scales and modes. Until then—

Good luck, and happy practicing!

An exercise to help guitarists\bassists that my teacher showed me when I was learning this stuff he called "target practice".

Unlike other instruments once you know the scale patterns in one key you know the scale patterns for all keys- they're the same you just have to know where to start and stop them. If you know a C scale and want to play a Db scale you just play the same pattern up one fret. The point of this exercise is learn where the roots are.

Play a C on the 6th string, then on the 5th string, then on the 4th, etc. There should be one C per string between the open string and the 12th fret. You don't need to do this fast though you'll be able to do it pretty quickly with a little practice.

Once you've played C on all 6 strings, continue to the next note until you've played through the entire circle of 5ths. Once you can do this and know the CAGED system you can play in any key.

Great article, I did have music lessons when I was young, but never really got to grips with music theory something I just acquired to replay over many years. I’ve ended up being a professional composer. There is just a certain fundamental logic about how the keys and notes work together I always wish I had better theory the theoretical grounding. It’s great to read this. !!